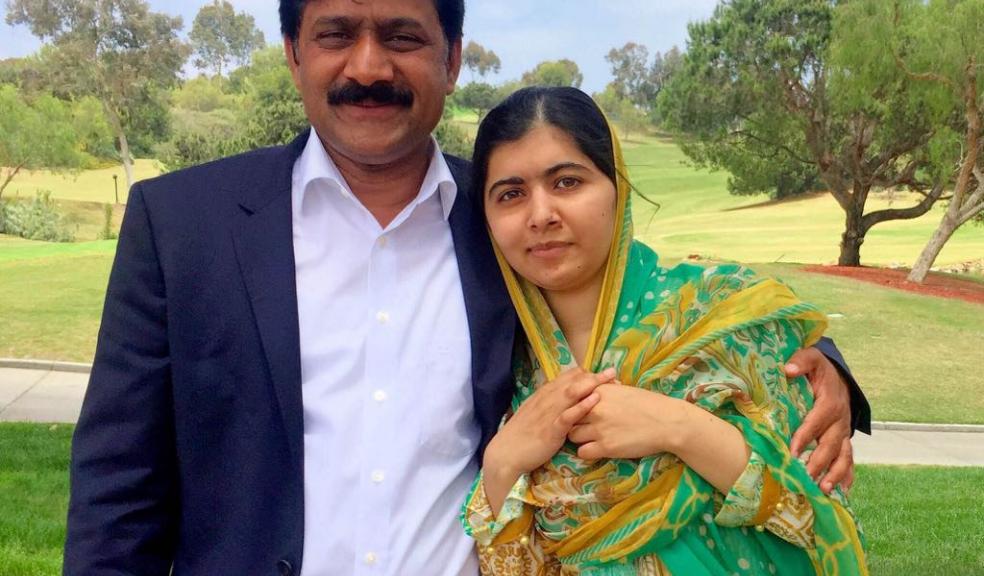

Malala's dad Ziauddin: I brought my daughter up to believe in herself and in equality

As children grow, they need more freedom and less protection from their parents. But giving them that freedom comes with risks.

The risks, however, are not normally as extreme as those faced by Malala Yousafzai, whose campaign to get girls educated in her native Pakistan led to her being shot in the head by a Taliban gunman at the age of 15. Airlifted to the UK for treatment, she survived, going on to become the youngest ever Nobel Peace Prize winner and is now studying for a degree at Oxford University.

Malala's activism and extraordinary characteristics were, at least in part, shaped by her equally extraordinary father Ziauddin Yousafzai, an education activist, human rights campaigner and teacher. Ziauddin, 52, rebelled against inequality at a young age, and founded a school for girls. When he had a daughter himself, he vowed Malala would have the same access to education as boys.

Ziauddin now lives in the UK with his wife Toor Pekai and their two sons, and has just written his memoir Let Her Fly, a moving account of fatherhood and his lifelong fight for equality.

Here Ziauddin, who is co-founder with his daughter of the Malala Fund , which invests in girls' education, discusses his book, parenting and equality, and living in the UK.

Did you and your wife's liberal views shape your daughter's own views?

"I always tell people when they ask me what's special about my mentorship for my daughter not to ask me what I did, ask me what I did not do. I did not clip her wings. I let her be herself. That's one part of my parenthood which is very important. I wanted my daughter to be independent and I encouraged my children to be themselves: to seek and strive in life for themselves. My wife Toor Pekai and I believe in freedom of thought and expression, and in our home environment we encouraged our three children to be strong, to believe in themselves, and to be free, and this has had a strong influence on our children."

Now you live in the UK what do you think about the way children are brought up in this country?

"When we were in Pakistan we had a great family life. Everybody had the right to speak what was on their minds and in their hearts and to share everything with one another. I have learnt a lot in the last seven years. The difficult part of my parenthood was with my sons and especially with my oldest son. When we came to the UK he was angry and emotional and wanted to play Xbox all the time! I had a difficult time with him until a family friend reminded me he was a teenager. She assured me he was going through changes and she was right. Now I am best friends with my sons.

"I appreciate the way children are brought up in this country. In Pakistan, there's a lot of patriarchy and religious influence. In the UK, children are raised for themselves rather than their parents. Parenthood isn't about the parents' past but about the children's future. Raising children in the UK is a very joyful experience; you let the children learn, you guide them, you advise them sometimes, but you don't impose yourself on them. I appreciate the opportunities that encourage children to become more independent and to look forward to the future."

What do you think British parents can learn by reading your book?

"Ours is the story of a family which has gone through a lot of difficulties but we believe that through our story of strength and togetherness, we can pass on beautiful values to families all around the world."

Has it been hard for you to convince your sons they are as special to you as Malala?

"In Pakistan, my eldest son told a friend that I was more focused on Malala. When I heard this, I was very sad but I told him I was sorry he felt that – he shouldn't feel that. My love for him is unconditional, but I also told him that for the rest of the world he has to earn love and respect – with his behaviour, his hard work, his brilliance.

"My children are very happy siblings, they love and respect one another. There is no feeling that Malala is a Nobel laureate or more special in the house. They argue and they fight like every family. Once somebody asked my youngest son how it feels growing up the brother of a Nobel laureate and he said that he doesn't know how it would feel to not have a Nobel laureate sister.

Are you and your family still frightened of the Taliban?

"This is a difficult question. Yes, we are frightened of the Taliban and the Taliban are frightened of us. Really, they don't like us because we believe in girls' education which they oppose, we believe in female empowerment which they can't see, we believe in culture, in music, in fine arts, and they don't believe in any such thing. They see us, especially Malala, as a symbol of change, a woman who gives courage and hope to other women of her country to stand up for their rights.

"When I say we're afraid of them, we're not afraid they will harm us. Pakistan is our home, it's the country of future generations so it really frightens us when we see more Talibanisation, when we see that democracy is weakened, liberal people being harassed and their liberty and their freedom of speech being taken away from them. That is frightening."

Do you still campaign for more equality in Pakistan?

"Things have changed in Pakistan a lot throughout my life. None of my five sisters went to school. Now, from the same village, there are 250 girls going to school and receiving quality education. A school has been built with Malala's Nobel Peace Prize money and the help of the Malala Fund. And that's not the only school, there are girls attending public school too. Now parents have different dreams for their daughters; they want to see them educated so they send them to school.

"I encourage our girls to receive more education and to believe in themselves, to be leaders because leaders bring about change. My message is that we will have a better, beautiful and more prosperous future if we believe in girls, in all women.

"Malala once beautifully said that we cannot succeed when half of us are held back. If we educate all girls for 12 years, we will add up to 30 trillion dollars to the world economy. We need to invest in girls' education. It will make our communities healthier, safer and wealthier."

It's been an incredible journey for your family. With hindsight, is there anything you would have done differently?

"It wasn't our choice to have an incredible journey; that's what makes it incredible. It wasn't planned, it wasn't well thought out. Even with hindsight, my view is the same – I couldn't have done things differently. The only option could have been that I remained silent about the right of girls to education and didn't raise my voice for peace, but that cannot be an option for me. That isn't me, nor my nature. It isn't Toor Pekai's nor Malala's nor my sons.

"The cruelties and atrocities that were inflicted by the Taliban were unbearable. I have sorrows, but I have no regret at all. What I did, what Malala did, we did everything for our human rights, for our land and for our people and we are proud of what we did."

Let Her Fly by Ziauddin Yousafzai is published by WH Allen, £9.99. Available now.